“Anti-Woke” Was Never About Ideas. It Was About Power.

By Brian Allen

This reporting is part of an ongoing examination of how political language translates into real-world policy outcomes.

The work does not stop with a single statement or viral moment. It continues as laws are passed, court challenges unfold, and measurable impacts emerge.

Readers who want to follow where this investigation leads next can do so through AllenAnalysis.

When Gavin Newsom said that “all this anti-woke stuff is just anti-Black,” he was not offering a hot take. He was describing an observable pattern that has now been documented across legislation, court rulings, education policy, voting access, and economic outcomes.

The phrase “anti-woke” presents itself as a cultural critique, but when translated into law and governance, its effects are neither abstract nor evenly distributed. They are concrete, measurable, and disproportionately borne by Black Americans.

This is not a matter of rhetoric. It is a matter of record.

The Rebrand

“Anti-woke” emerged in the late 2010s as a replacement for language that had become politically radioactive. Explicit opposition to civil rights, desegregation, or racial equity had lost mainstream viability. What replaced it was a vocabulary of grievance that framed racial inclusion as excess, fairness as favoritism, and historical reckoning as ideological threat.

The shift was strategic. Political scientists have long documented how coded language functions as a substitute for explicit racial appeals once those appeals become socially unacceptable. This phenomenon, known as racial priming, allows policies with racialized outcomes to be sold as neutral governance.

The modern “anti-woke” framework fits squarely within this lineage.

Where the Policies Land

The clearest way to test Newsom’s claim is not through intent but through impact.

Voting Access

Since 2021, at least 14 states have passed laws that restrict voting access, including reductions in early voting, limits on mail ballots, stricter voter ID requirements, and criminal penalties for minor registration errors.

According to the Brennan Center for Justice, these laws disproportionately affect Black voters, who are more likely to rely on early voting and same-day registration due to work schedules and historical barriers to polling access.

Source: Brennan Center for Justice, Voting Laws Roundup (2021–2024)

Federal courts have repeatedly found that several of these laws were enacted with knowledge of their racial impact, even when race was not explicitly cited in the statutory language.

“The legislature knew which voters they were targeting and chose methods that would disproportionately burden Black voters.”

Federal District Court opinion, North Carolina voter ID litigation

Education and Curriculum Bans

So-called “anti-woke” education laws have focused heavily on restricting how race, slavery, segregation, and systemic discrimination can be taught in public schools.

Since 2021, more than 20 states have passed laws or administrative rules limiting discussions of racism, implicit bias, or structural inequality in K-12 and higher education.

The consequences are not evenly distributed.

A 2023 report from the Government Accountability Office found that schools serving predominantly Black students were significantly more likely to face curriculum audits, funding threats, or administrative intervention under these laws.

Source: U.S. Government Accountability Office, Civil Rights and Education Oversight (2023)

The result is not neutrality. It is enforced silence around Black history and Black civic experience.

Economic and Workplace Effects

“Anti-woke” legislation has also targeted diversity, equity, and inclusion programs in both public agencies and private companies.

States including Florida and Texas have banned or defunded DEI initiatives in public universities and government offices. These programs were originally created to address documented disparities in hiring, promotion, and pay.

The data underlying those disparities has not changed.

According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, Black workers continue to earn approximately 76 cents for every dollar earned by white workers, even after controlling for education and experience.

Source: U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, Earnings Data (2024)

Rolling back mechanisms designed to address these gaps does not create neutrality. It preserves the imbalance.

Criminal Justice and Policing

Perhaps the most direct throughline appears in criminal justice policy.

States that have embraced “anti-woke” rhetoric have been more likely to roll back police accountability measures enacted after 2020, including civilian oversight boards, use-of-force reporting requirements, and consent decree compliance.

The Department of Justice has documented that Black Americans are still more than three times as likely to be subjected to police use of force.

Source: U.S. Department of Justice, Use of Force Data Collection (2023)

Framing accountability as “woke excess” has had the practical effect of insulating systems that already produce racially disparate outcomes.

The Pattern

Taken individually, each of these policies is defended as an administrative preference or ideological disagreement. Taken together, they form a consistent throughline.

When “anti-woke” becomes law:

• Voting becomes harder for Black communities

• Black history becomes more restricted in classrooms

• Workplace protections addressing racial disparities are dismantled

• Police accountability mechanisms are weakened

Why the Language Matters

Calling this dynamic “anti-Black” is not rhetorical escalation. It is analytical clarity.

A policy framework that repeatedly produces racial harm does not become neutral simply because it avoids racial language. Civil rights law itself is built on this principle. Courts evaluate impact, not just stated intent.

The Supreme Court has affirmed this standard repeatedly in voting rights, housing discrimination, and employment law.

If outcomes are racially disparate and policymakers proceed with full knowledge of those outcomes, the distinction between ideology and discrimination collapses.

The Bottom Line

“Anti-woke” was never a philosophy. It was a rebrand.

It took familiar power arrangements, wrapped them in grievance, and sold regression as reform. The language softened. The results did not.

Gavin Newsom said the quiet part out loud. The data says the rest.

This investigation is part of a larger body of work at The Allen Analysis.

We publish document-driven reporting focused on accountability, not access, and we do not stop at the first story.

If this kind of journalism matters to you, consider subscribing to follow where this reporting leads next.

Footnote:

[1] Brennan Center for Justice.

Voting Laws Roundup: December 2021–2024.

https://www.brennancenter.org/our-work/research-reports/voting-laws-roundup

[2] North Carolina State Conference of the NAACP v. McCrory, 831 F.3d 204 (4th Cir. 2016).

Federal appellate ruling finding that lawmakers targeted Black voters “with almost surgical precision.”

[3] U.S. Government Accountability Office (GAO).

Civil Rights Oversight in Education: Federal Monitoring of State Curriculum Restrictions. GAO-23-105799 (2023).

https://www.gao.gov/products/gao-23-105799

[4] U.S. Department of Education, Office for Civil Rights.

Data Snapshot: Disparities in Educational Access and Discipline. (2022–2024).

https://www.ed.gov/about/offices/list/ocr

[5] U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics.

Earnings and Wages by Race and Ethnicity. (2024).

https://www.bls.gov/opub/reports/race-and-ethnicity/

[6] Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC).

Workplace Discrimination and Systemic Bias Reports.

https://www.eeoc.gov/statistics

[7] U.S. Department of Justice.

Use of Force Data Collection, 2023 Annual Report.

https://www.justice.gov/crs/use-force

[8] Floyd v. City of New York, 959 F. Supp. 2d 540 (S.D.N.Y. 2013).

Landmark federal case establishing disparate impact standards in policing practices.

[9] Village of Arlington Heights v. Metropolitan Housing Development Corp., 429 U.S. 252 (1977).

Supreme Court precedent affirming that discriminatory impact and contextual evidence are relevant even absent explicit racial intent.

[10] Shelby County v. Holder, 570 U.S. 529 (2013).

Supreme Court decision weakening federal preclearance protections and enabling state-level voting restrictions.

Read More:

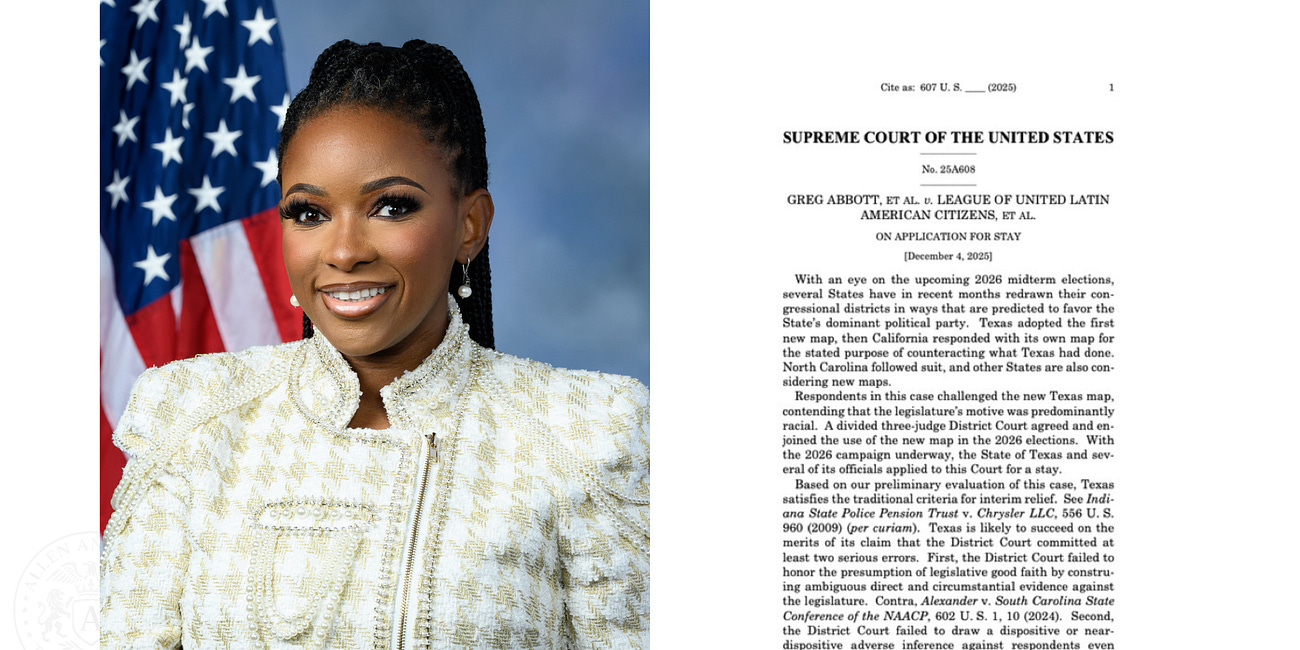

Jasmine Crockett Didn’t Lose a Race. The Supreme Court Moved the District.

When voters in Dallas sent Jasmine Crockett to Congress, they did not just elect a Democrat.

Outstanding policy analysis connecting language shifts to measurable outcomes. The 'surgical precision' phrase from that NC court ruling really captures how these laws target specific communities while maintaining plausible deniability through coded rhetoric. We're seeing the same pattern in tech where 'merit-based' hiring policies systematicaly reduce diversity without stating that goal explictly, and the impact is undeniable even when the intent stays buried in meeting notes.