Trump Proposal to Rename the Kennedy Center Raises Questions About Presidential Power and National Memory

By Brian Allen

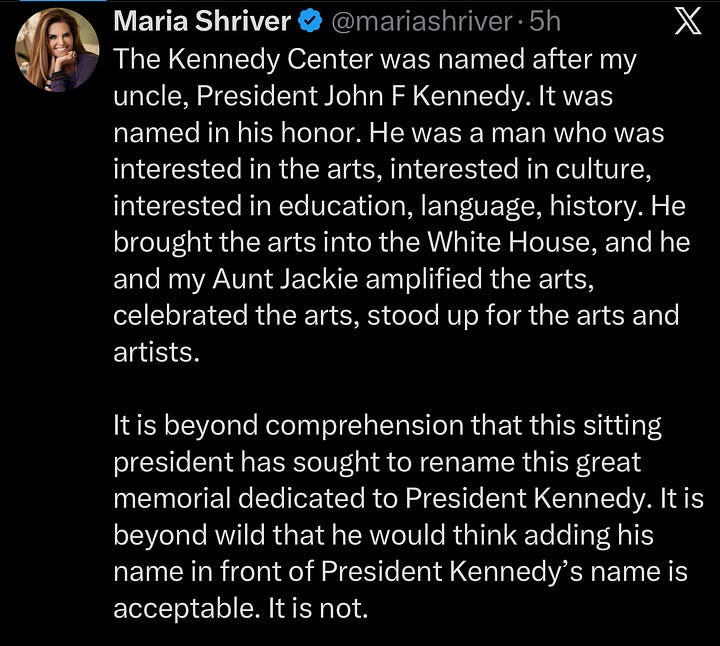

Maria Shriver’s public rebuke of President Trump over reports that he has sought to rename or rebrand the Kennedy Center goes beyond a family objection or a cultural dispute. It exposes a deeper and more consequential issue: how far a sitting president can go in reshaping national institutions to reflect personal identity, and what happens to shared civic memory when that line is tested.

At stake is the John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts, a federally chartered institution named by Congress to honor the 35th president. Shriver, Kennedy’s niece, framed the controversy in stark terms, calling it “beyond comprehension” that a sitting president would consider inserting his own name into a memorial dedicated to another president. Her warning was not sentimental. It was structural.

This is not about aesthetics or tradition for tradition’s sake. It is about the boundaries of presidential authority, the meaning of public memorials, and whether national institutions belong to the country as a whole or to the individual temporarily occupying the Oval Office.

What is being proposed and what is known

According to public reporting and statements circulating among administration allies, President Trump has expressed interest in renaming or rebranding the Kennedy Center in a way that would add his name or otherwise diminish Kennedy’s singular association with the institution. No formal executive order or legislation has been introduced. But the seriousness of the reaction reflects the fact that the Kennedy Center is not a discretionary presidential project.

The Kennedy Center was designated by Congress in 1964 as a national memorial to President Kennedy. Its name, purpose, and governance are embedded in federal statute. While presidents serve as honorary chairs of its board and appoint trustees, they do not own the institution. That distinction is central to why the proposal has generated concern even in the absence of formal action.

Shriver argues that once the idea is entertained, the limiting principle becomes unclear. If one president can rebrand a memorial honoring another, the restraint that has governed national memory for decades is no longer operative.

Why the Kennedy Center occupies a unique role

The Kennedy Center is not analogous to a presidential library, which is typically funded privately and built after a presidency has ended. It is a living national institution, funded in part by taxpayers, governed by law, and intended to endure across generations.

It also occupies a symbolic role that extends beyond politics. The Center was conceived as a space for arts, culture, and international exchange, reflecting Kennedy’s belief that cultural diplomacy and artistic expression were integral to national identity. Presidents of both parties have respected that role, even during periods of intense political division.

Altering the name or branding of the Kennedy Center would therefore represent more than a cosmetic change. It would signal that no national institution is insulated from personalization by executive power.

Shriver’s argument centers on dignity and stewardship

Shriver’s statement is notable for its tone. She does not attack Trump’s policies or political ideology. She does not frame the issue as partisan. Instead, she appeals to the dignity of the presidency and the idea of stewardship.

When she says such a move would be “beneath the stature of the job,” she is articulating a widely shared but often unstated norm: that presidents inherit institutions they did not create and pass them on largely intact. The presidency, in this view, is a caretaker role, not an ownership stake.

That framing matters because it situates the controversy within a long tradition of restraint that has governed how power is exercised in symbolic spaces.

A broader pattern of personalization

The Kennedy Center dispute fits into a broader pattern during Trump’s presidency. Repeatedly, institutional settings have been used to project personal narratives or settle political scores, from the reworking of historical displays inside the White House to the rebranding of congressionally approved programs as personal presidential initiatives.

Each instance can be defended in isolation. Together, they suggest a governing philosophy in which institutional authority flows upward into the persona of the president rather than remaining anchored in the office itself.

The concern raised by Shriver is that this approach does not stop at policy. It extends into memory, symbolism, and the meaning of national space.

Legal authority versus institutional norms

Legally, Trump’s ability to rename the Kennedy Center outright is constrained. The Center’s name is established in federal law, and any formal change would almost certainly require congressional action. Even significant rebranding could provoke legal and institutional resistance from the board of trustees.

But legality is not the primary issue. Many of the most important limits on presidential behavior are not codified. They are enforced by precedent, mutual restraint, and shared understanding.

Presidents have generally avoided attaching their names to national memorials not because it is always illegal, but because it violates an understood boundary between personal ambition and public inheritance.

Once that boundary is crossed, the question is no longer what the law allows, but what the presidency normalizes.

Why national memory is at stake

Public institutions like the Kennedy Center serve as anchors of shared memory. They reflect collective decisions about what and whom the nation chooses to honor. When those anchors become subject to personal revision, the stability of that memory weakens.

The risk is not that one name changes. It is that history becomes provisional, revised by each administration according to its own preferences. Over time, that erodes public trust in institutions as neutral custodians of national identity.

Countries that allow leaders to personalize monuments and memorials often find that those institutions lose legitimacy once the leader leaves office. What remains is a cycle of renaming and erasure that turns history into a battleground rather than a reference point.

The logic Shriver is warning against

Shriver’s hypothetical examples of renaming JFK Airport or the Lincoln Memorial are not predictions. They are illustrations of logic taken to its conclusion.

If a sitting president can insert his name into a memorial honoring another president, the restraint that prevents similar actions elsewhere rests on nothing more than goodwill. Once goodwill is no longer assumed, every institution becomes contestable.

That is the structural concern at the heart of this controversy.

Why this resonates beyond the Kennedy family

It would be easy to dismiss Shriver’s comments as familial protectiveness. But the response to her statement suggests something broader. The Kennedy Center is a public institution. Its name and mission belong to the country, not to any one family or administration.

The unease surrounding this proposal reflects a growing anxiety that no civic space is immune from political branding. For some, that is a welcome disruption of elite norms. For others, it signals a departure from the idea that certain institutions should remain above personal rivalry.

The presidency as a temporary trust

At its best, the presidency is understood as a temporary trust. Presidents shape policy and influence culture, but they do so within a framework designed to outlast them. They leave monuments largely as they found them, recognizing that history does not belong to the present alone.

Shriver’s intervention is a reminder of that principle. It is not an argument for preserving Kennedy’s legacy at all costs. It is an argument for preserving the idea that national memory is not a personal asset.

Bottom line

The proposal to rename or rebrand the Kennedy Center is not a trivial cultural skirmish. It raises fundamental questions about the limits of presidential power and the stewardship of national memory.

If national institutions can be reshaped to reflect the identity of a sitting president, the presidency shifts from a role of custody to one of possession. That shift would not end with one building or one name. It would redefine how Americans understand the relationship between power, history, and the state itself.

Once that line is crossed, restoring it is far harder than defending it in the first place.

MORE:

Pelosi’s Successor Race in San Francisco Pits Scott Wiener Against Saikat Chakrabarti, Testing the Democratic Party’s Direction

Nancy Pelosi’s decision to step aside after nearly four decades in Congress has done more than open a safe Democratic seat in San Francisco. It has triggered a primary contest that functions as a stress test for the Democratic Party itself: its governing instincts, its ideological boundaries, and its ability to reconcile institutional competence with a …

Trump’s $1,776 “Warrior Dividend” Is a Rebranded Housing Subsidy, Not New Money

Washington, D.C —President Trump’s announcement that more than 1.45 million service members will receive $1,776 checks before Christmas was framed as a personal reward for troops. In reality, the payments come from existing funds Congress specifically allocated to subsidize military housing, according to a senior administration official who confirmed th…

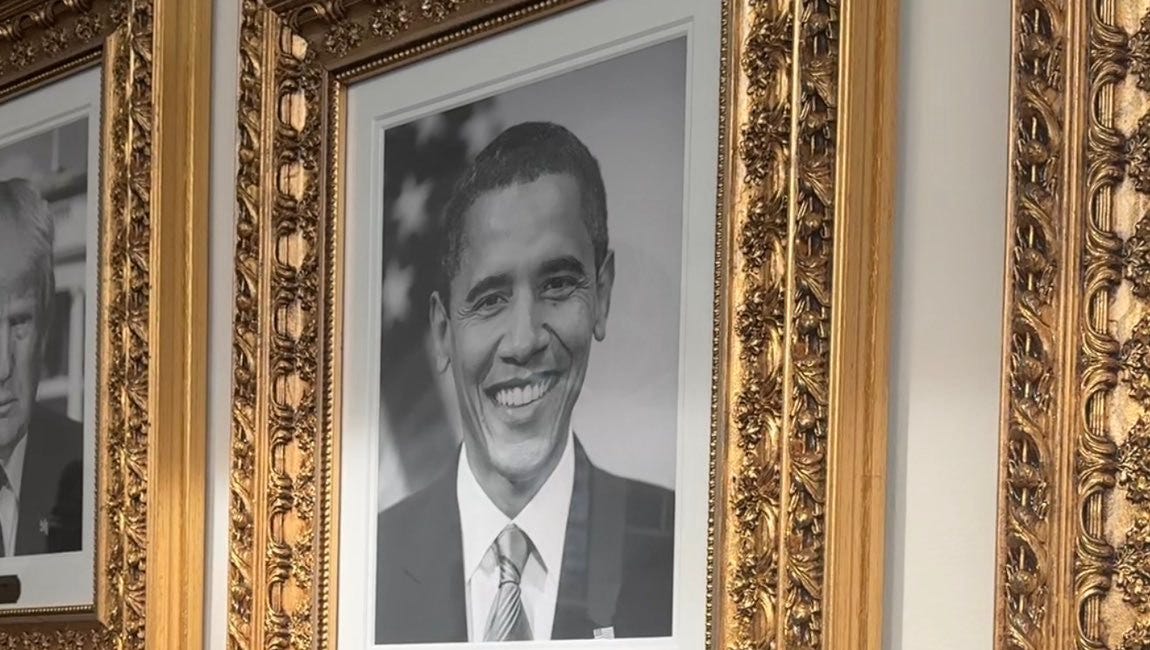

White House Adds Partisan Plaques to Biden and Obama Portraits

The White House has installed new plaques beneath the official portraits of former Presidents Joe Biden and Barack Obama that sharply criticize their records, transforming a traditionally nonpartisan historical display into an overt political statement.

The White House Just Threw Admiral Frank M. Bradley Under the Bus

This Substack is reader-supported. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.